You Know Ho Is Burning but Then Again

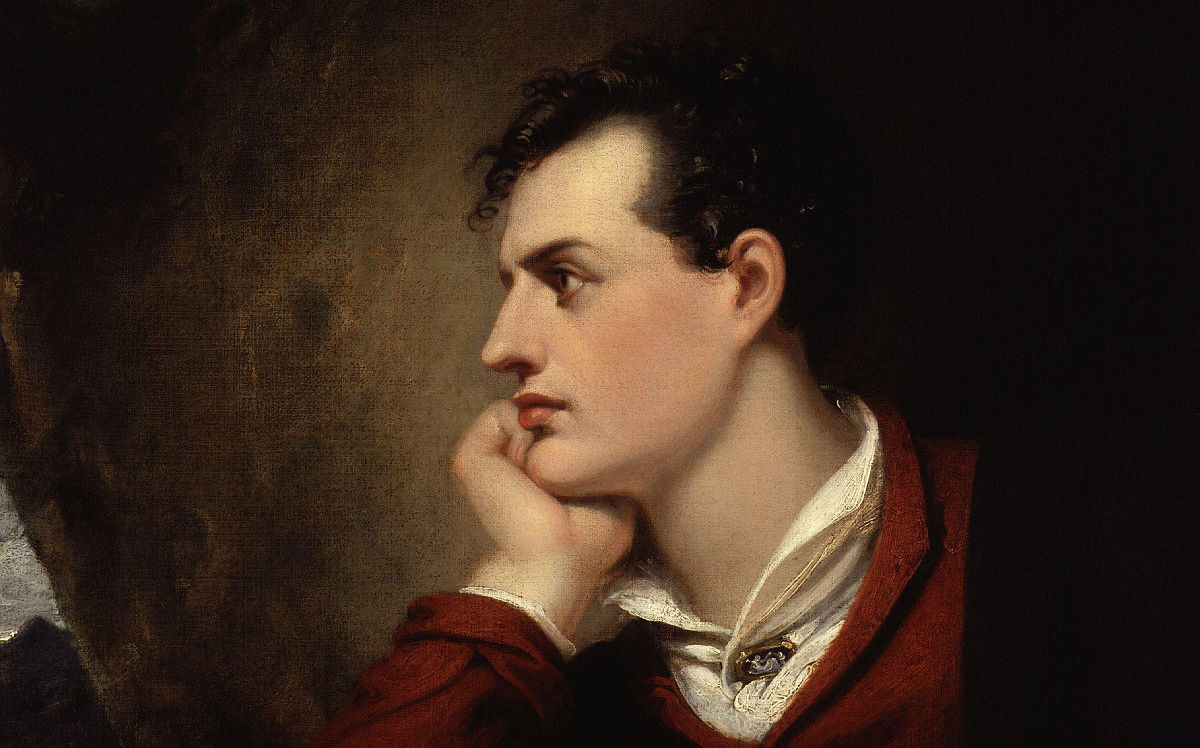

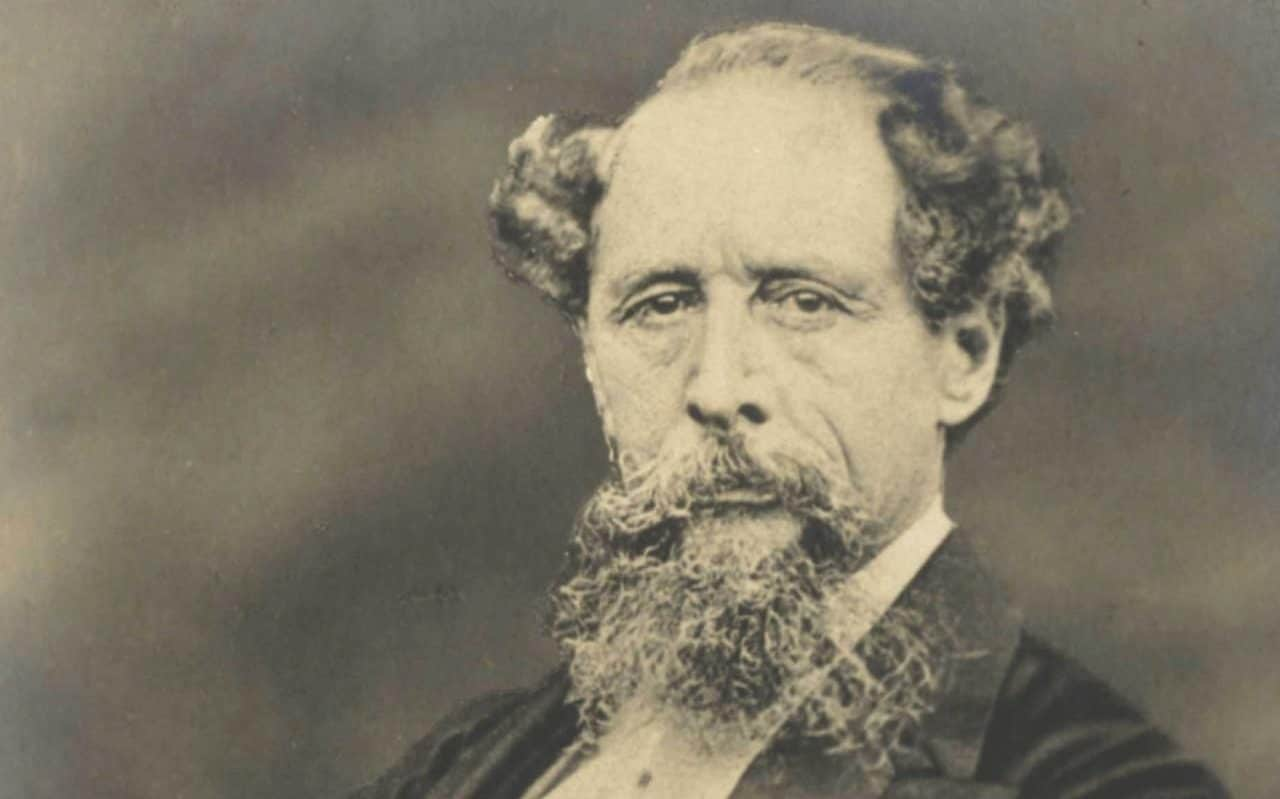

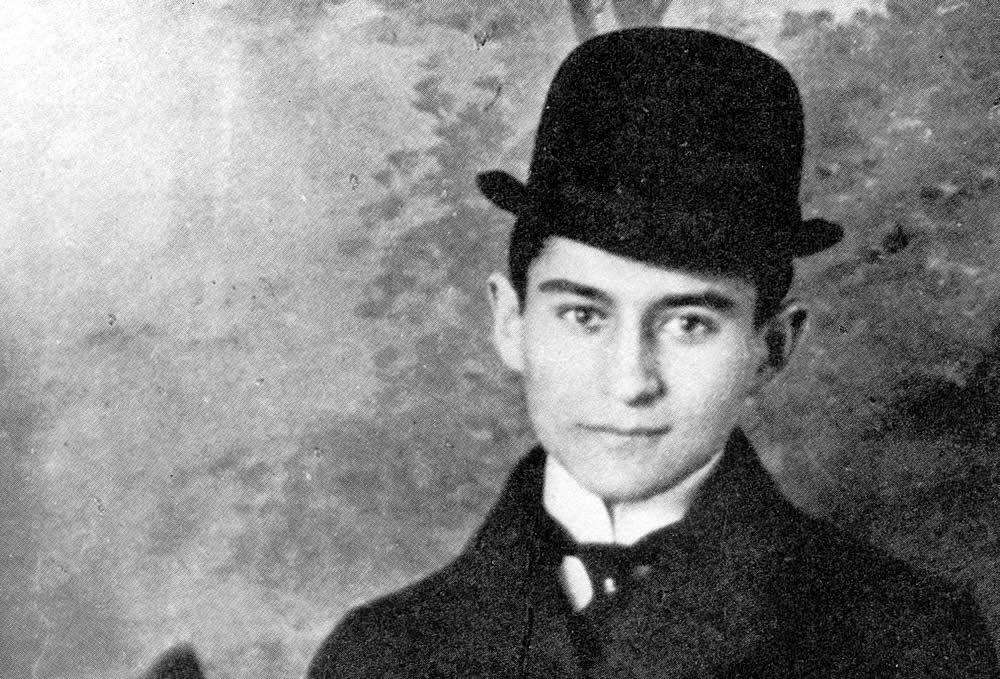

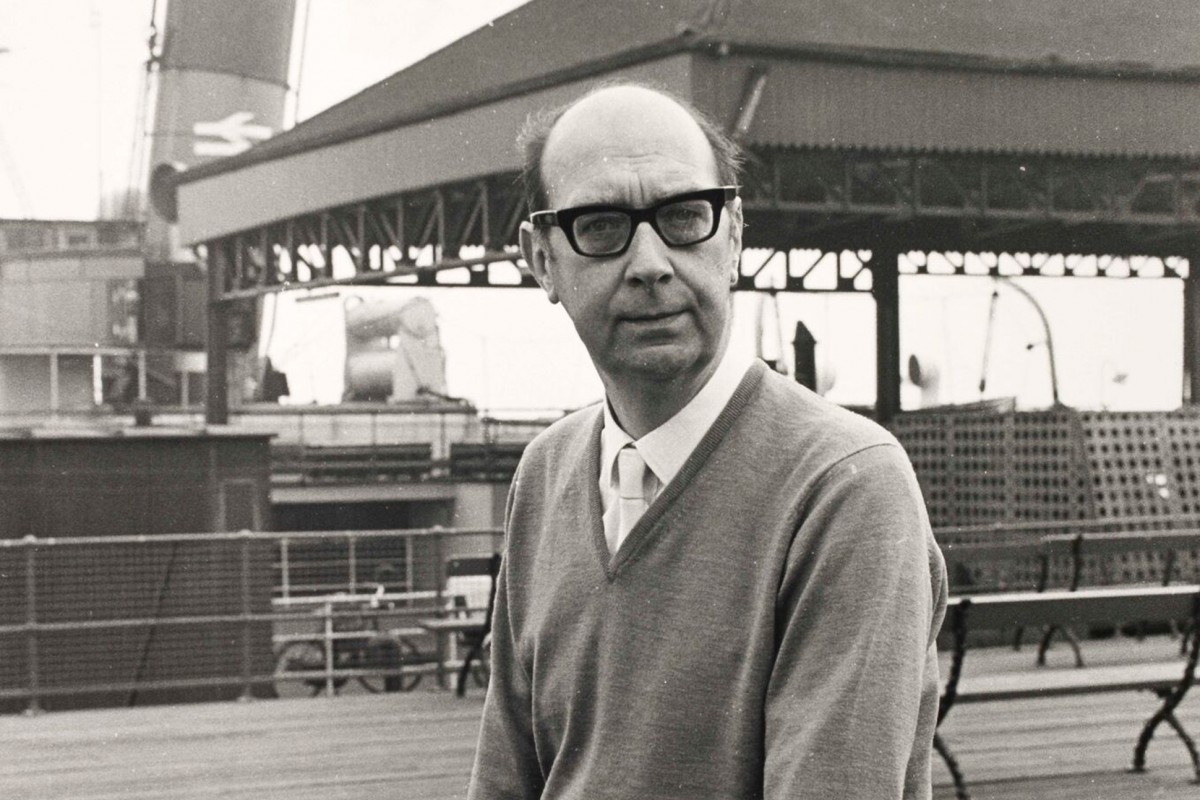

"Manuscripts don't burn," says the devil in Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, pulling ane that everyone idea had out from under his enormous talking cat. Of course they don't, 1 might call back. Well, not anymore, anyhow. After all, these days so many books are written directly into the deject that burning would seem nearly impossible—barring the global crash that is almost definitely coming if we stay on our current path. Perhaps that's why legends of destroyed manuscripts linger so long in the literary imagination—we're beginning to forget the truth that anything might be lost forever. And of grade, manuscripts doburn down. Simply manuscripts can also hide when they were idea to accept burned, only to be discovered years later in a drawer in someone's sitting room, secreted there or merely forgotten. They can pass up to burn down—or rather, someone can refuse to burn them. They can be burned accidentally, or later a long, desperate boxing. Here, I've collected 10 stories of the devastation (or threat thereof) of unpublished works, diaries and letters by notable authors—texts, in other words, of involvement to the earth. Some prove immortal, others duly destroyed, and some others alive on in ghost-like forms, re-created, ostensibly imperfectly, by their makers. We may exist at the terminate of stories similar these, given the cloud and all, which makes them experience more resonant. I dubiousness fifty-fifty in the time to come anyone will be reading ten stories of the epic hard-drive failures of famous authors. But and so once again, who knows? Read on, while you can. Lord Byron, Diaries Byron was famously mad, bad, and dangerous to know—and and then, information technology seems, were his memoirs, which his friends deemed so salacious, so potentially dissentious to his reputation and to those of his ex-wife and daughter, that they decided to destroy them in an act sometimes described as "the greatest crime in literary history." Here it is, every bit dramatized by Benita Eisler in theNew York Times: On Monday, May 17, 1824, near noon, half-dozen men gathered in the high-ceilinged cartoon room at l Albemarle Street, off Piccadilly, in a house that served as both dwelling house and function to the publisher John Murray. For days the group had been quarreling amongst themselves. Alliances shifted. Letters flew back and forth, and meetings between pairs connected through the morning. One time they were finally assembled, an argument flared between two of their number, John Cam Hobhouse, a rising immature parliamentarian from a wealthy Bristol family, and Thomas Moore, a Dublin-born poet and grocer's son. Angry words threatened to turn into physical violence. Finally, the decision of the host prevailed, and at-home was restored. Murray then asked his xvi-year-one-time son to join them. Introduced every bit heir to his male parent's business, the male child was invited to witness a momentous event. A servant appeared, carrying two bound manuscript volumes. While the group drew closer to the burn blazing in the grate, ii others, Wilmot Horton and Colonel Doyle, took the books and, tearing them apart, fed the pages, covered with handwriting familiar to all those present, to the crackling flames. Within minutes, the memoirs of George Gordon, 6th Lord Byron, were reduced to a mound of ashes. Of course, this is unbearably tantalizing: what was so terrible that his friends resolved to destroy the bear witness? And how would nosotros feel about it today, if we knew? Maybe nosotros never will, just then again—y'all know what they say near manuscripts. Thomas Carlyle,History of the French Revolution Here'south a tip: if you want to salvage yourself a lot of trouble, don't lend out your books. Or actually, just don't lend out your unpublished manuscript, the one you've been working on for months, especially when it's your just copy. In 1835, Thomas Carlyle asked his friend John Stuart Manufacturing plant to read his draft ofHistory of the French Revolution—the volume he thought would "finally make his literary reputation"—but one night, Factory came to his door to admit a horrible truth: a maid had mistaken the manuscript for waste paper, and burned information technology. Merely was that actually the truth? Equally Rachel Cohen writes inThe New Yorker, Even at the beginning, Carlyle must have had, every bit we practice, certain questions. Mill's house was full of valuable manuscripts; why would a maid just seize the commencement pages she saw and use them for kindling? Mill seems to take put them in a pile intended for waste matter; was there annihilation backside his carelessness? Was he jealous of Carlyle's accomplishment, or dismayed that Carlyle had represented the coming of democracy so differently than Factory would have? After all, Manufacturing plant had once wanted to write a book on the same topic, which is suspicious. Merely it didn't thing, in the stop—after a hard start, Carlyle rewrote the book, and when information technology was published in 1837, Mill wrote a glowing review: "no work of greater genius, either historical or poetical, has been produced in this land for many years." Except maybe for the first version. Nikolai Gogol,Dead Souls (Part Two) In 1841, the publication of the get-go part of Expressionless Souls made Gogol a literary titan—but while he worked on role two for the rest of his life (we call back), no one volition ever come across it, because Gogol burned the pages soon before his death. As for why exactly he did and so, reports differ. Towards the end of his life, Gogol turned towards religion, and his asceticism increased under the influence of Father Matvey Konstantinovsky. He renounced some of his before piece of work, tearing some of information technology upwardly. Some speculate that he had begun to detect it sinful, and that Konstantinovsky urged him to burn part ii of Dead Souls as well. But it's also possible that information technology was simply an accident. According to V. Five. Gippius's biography of Gogol, on the night of Feb 24, 1852 (February 11, Erstwhile Way), the author took a bundle of "notebooks tied with a ribbon, placed it in the stove, and lit it with a candle." His servant begged him to end, but Gogol told him that information technology was none of his concern, and that he should pray. Meanwhile, the burn down had gone out after scorching the corners of the notebooks. Gogol noticed this, removed the sheaf of papers from the stove, undid the ribbon, and, arranging the pages in such a manner that they would catch more easily, again set them afire, and sat in a chair before the burn down, waiting until everything had burned to ashes. Then, crossing himself, he went back into the room he had come from. He kissed his servant, lay down on the couch, and began to cry. Evidently, Gogol wasn't even sure which of his papers he had burned. In the morning, he reportedly said, "Just imagine how powerful the evil spirit is! I wanted to burn some papers I had intended to burn long ago, but instead I burned the chapters ofDead Soulswhich I wanted to go out my friends to call back me past after my decease." Nine days afterward, he was dead. Charles Dickens,Messages In September of 1860, Charles Dickens congenital a bonfire behind his house at Gad's Hill and threw in "the accumulated messages and papers of xx years"—probably, as Paul Lewis wrote in The Dickensian, over 10,000 discrete pieces. "They sent upwardly a smoke like the Genie when he got out of the casket on the seashore," he wrote, "and as it was an exquisite day when I began, and rained very heavily when I finished, I suspect my correspondence of having overcast the face of the Heavens." His caption was that he was "shocked by the misuse of private letters of public men" and afterward began to fire almost all his correspondence. Lewis speculates that the action had to do with the embarrassing publication of a letter of the alphabet he had written to a friend about his separation from his wife (and the "virtuous and spotless" young lady who was definitely not involved); others indicate out that he may have been directly worried about the outing of his relationship with his teenage mistress, or that he was simply at a turning point, looking away from the past and towards the hereafter. Which doesn't explain why he kept up the burning, so I'm putting my coin on the mistress. Franz Kafka,The Trial Finally, a writer who did non succeed in called-for all of his manuscripts—despite the fact that information technology was his dying wish. Towards the cease of a long battle with tuberculosis in 1924, Kafka asked his all-time friend Max Brod to burn all of his papers later his death: "Honey Max, my final request: Everything I leave behind me . . . in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my ain and others'), sketches, and and so on, [is] to be burned unread." Brod agreed—but he didn't do information technology. Instead, he edited and posthumously published much of his friend'south piece of work, includingThe TrialandThe Castle. In 1939, Brod fled the Nazis to Tel Aviv, bringing with him the rest of Kafka's manuscripts. There, he began a relationship with his secretary Esther Hoffe, and upon his death in 1968, left the papers to her. (She was meant to publish and protect them, but she too disobeyed her directive, selling the original manuscript ofThe Trialfor $2 million.) Subsequently her death, a 42-yr legal battle ensued—her daughters claimed that the papers were theirs, just the courts eventually awarded the manuscripts to the National Library of Israel, deciding that "Brod's last wish was that his life's work, his material legacy, should be entrusted in its entirety to public archives." The National Library of State of israel now plans to digitize the works and make them bachelor to the public—the polar opposite of burning them. Mikhail Bulgakov,The Chief and Margarita Famously, Bulgakov burned the manuscript of his masterpiece, The Master and Margarita in 1930, in despair later 2 years of work—only to begin writing it once more from scratch the following year. He would work on it in hush-hush—such anti-establishment works were not tolerated in Stalinist Russia—for the rest of his life, indeed nigh correct up to the terminate, though the book wouldn't run across full publication until xx-vi years after his death. The eponymous Principal, of course, a parallel to Bulgakov in a number of ways, likewise burns his own book in frustration, simply to accept it handed dorsum to him past Woland (a.k.a. the devil) with the now-famous phrase: "Manuscripts don't burn." OnlyThe Master and Margaritawasn't the only manuscript that Bulgakov unsuccessfully burned. According to J.A.Eastward. Curtis'sManuscripts Don't Burn: Mikhail Bulgakov: A life in letters, in 1926, in the grade of an investigation into i of his acquaintances, the OGPU (the pre-KGB KGB) confiscated some of Bulgakov'due south papers, including his diaries and the manuscript ofThe Heart of a Dog. Bulgakov demanded that they be returned, merely he only got them back three years later, at which point he "immediately burned the diaries and resolved never to go on a diary over again. Since that time, it had been assumed that the diaries were lost, until the advent of glasnost prompted the KGB to acknowledge that, in fact, the OGPU had fabricated a copy of at least function of the diary back in the 1920s, and this was still sitting in the KGB'due south archives." It was published in 1989. Edna St. Vincent Millay,Conversation at Midnight When Edna St. Vincent Millay went on holiday to Sanibel Island, Florida, in 1936, she naturally brought her manuscript-in-progress—years in the making—along with her. She had her luggage sent up to her room and went down to the embankment to expect for shells. When she turned dorsum, she saw that her hotel was in flames, the manuscript along with information technology. She went domicile and rewrote the book from memory, and it was published the next year. Malcolm Lowry,In Anchor to the White Sea In 1944, Malcolm Lowry was living on the coast of British Columbia with his second wife when his cabin defenseless fire and burned to the basis. Lowry leapt into the flames in an endeavour to save his manuscripts—a burning log roughshod on his back and "fried" him, simply he managed to rescue the pages that would becomeUnder the Volcano. However, hisIn Anchor to the White Sea, "that thousand-folio Paradiso" (toNether the Volcano's Inferno) was lost, and Lowry died xiii years later without always re-creating it. It wasn't until 2000 that hisfirstwife, January Gabrial, revealed that she had had a secret re-create ofIn Ballast to the White Oceanthe whole time. Lowry had left information technology with Gabrial's mother in 1936, and likely forgotten about it completely. In 2003, two years later Gabrial's expiry, the executor of the manor gave the manuscript to the New York Public Library, and it was published in 2014. Fun fact: this wasn't the first novel that Lowry lost. The manuscript of his first novel,Ultramarine, was stolen out of his publisher's auto—the top had been left open—and he claimed he had to rewrite the whole thing in a manner of weeks. (Though others claim there was a carbon copy.) V. S. Naipaul, various manuscripts At some bespeak in the 1970s, Naipaul deposited his papers and unpublished manuscripts to Ely'south, a London warehouse, for safekeeping. Patrick French, Naipaul's biographer, counts amidst this trove . . . the novel he had begun in Trinidad in 1949, the manuscript ofThe Shadow'd Livery, his translation ofLazarillo de Tormes, his scripts for the BBCCaribbean area Voices, his diaries from his years at Oxford, his journals forThe Center Passage, the manuscripts and typescripts of all the books he had written before moving to Wiltshire, notes and messages from his first trip to India in 1962, well-nigh of the letters he had received in the 1950s and '60s, his own "Letters from London" for theIllustrated Weekly of India, his travel journals from Africa in 1966, and the notebooks and diaries of his early journalism. But in 1992, when Naipaul and his wife tried to arrange for the annal to exist valued, it had disappeared. Or to be more precise, it had been incinerated due to a clerical error. Ely's had, at some point, destroyed all of the boxes marked "NITRATE"—and all of the boxes marked "NAIPAUL" had gotten swept upwardly too. That's a pretty major failure of reading comprehension. Philip Larkin, Diaries Earlier his death in 1985, Philip Larkin asked one of his mistresses, Monica Jones, to destroy his diaries. For whatever reason, according to John Banville Jones asked some other mistress, Betty Mackareth, to practice it. Betty took the thirty-odd volumes into Larkin's office in the Brynmor Jones Library at Hull University and fed them folio by page into a paper shredder—the task took all afternoon. With feature loyalty and discretion, she did not attempt to read the diaries before destroying them, "but I couldn't help seeing lilliputian $.25 and pieces. They were very unhappy. Desperate, really." Larkin had told his time to come biographer Andrew Motion, "When I meet the Grim Reaper coming upward the path to my front door I'm going to the lesser of the garden, like Thomas Hardy, and I'll have a bonfire of all the things I don't want anyone to see"; yet, the blaze was never built, and according to Motion, the diaries, "viii manuscript books in which he drafted his poems, and the big mass of his unpublished papers and letters lay undisturbed in his house when he was carried out of information technology for the concluding time." Of course, non all of that was destroyed—selections of Larkin'due south previously unpublished poems and messages have been coming out ever since. But the diaries, it seems, are gone.

Source: https://lithub.com/10-tales-of-manuscript-burning-and-some-that-survived/

Post a Comment for "You Know Ho Is Burning but Then Again"